My friend, an unaffiliated-to-fashion but in-the-know fan of clothing, overheard me talking about

Vetements with a fashion editor last weekend, so she asked, “What’s Vetements?”

I explained that it was a recent fashion phenomenon, a new design collective that has stopped the industry short, become its new darling and turned on its head all the basic principles that fashion has set for itself as a commander of taste. It functions as a deeply reactive entity that rejects the

ateliers of Paris with their fanciful ideas of what women

should look like and responds instead to what a new generation of women already

do look like. (Also, they sell

DHL t-shirts for $330; you can request one from the de facto delivery service for $14.99.)

It’s fantasy versus reality — kind of like comparing the show

Sex and the City to

Girls wherein Vetements is

Girls: rooted in what’s real and true, whether good or bad, and not interested in the Galliano-esque suspension of disbelief and reverie of fiction.

This isn’t actually problematic until you consider the implications of the house’s designer, Demna Gvasalia, accepting a position as the creative director of at one of the aforementioned ateliers, Balenciaga.

Reviewers for some venerated publications —

Vogue,

The Times,

Washington Post — have declared Vetements the house to breathe new life into fashion. It’s the industry’s pièce de résistance. But it’s not just a press toy. Luxury vendors who stock the collection —

Net-A-Porter,

Browns Fashion,

Matches and so forth — indicate that it sells very, very well. Go ahead right now; try to order

a pair of shoes.

But here’s the thing: I don’t get the fanfare. You want to lose your shit over clothes that make you feel like 18th century royalty while you’re washing the dishes in real life, I totally get that. But to wear clothes that make you

feel like you’re about to wash dishes? Where’s the grand illusion there?

The clothes are not very practical, either, which is perhaps the cerebrally-perverse point of a collection that is responding to real life instead of creating its own world, but given how expensive they are (

reconstructed Levi’s jeans range from $1,040 to $1,500), who are the people who are buying in? Am I missing something?

I do understand what the house is trying to do, and don’t doubt the talent — Gvasalia spent time at

Margiela in the earlier aughts and those were glory days. Today, the deconstructed, reconstructed metaphor for an industry that is fledgling but trying to hold it together does not get lost on me. The reactive nature of the house and subsequent embracement by industry heavyweights is a sharp, promising turn in the direction of a more democratic fashion industry. Here, here to all that.

But when you think of what we’re called by the naysayers — a manipulative beast that makes you feel less-than so that you’ll buy and become more-than — does Vetements support or counter that clause?

Among shoppers, there have always been

those who buy clothes (think

Brunello Cucinelli,

Loro Piana, the good quality stuff that hugs you) and those who buy energy (Saint Laurent is commodified “cool,” ditto that for

Alexander Wang; Phoebe Philo sells you simplicity, a lack of complication but a healthy serving of complexity).

Those who

make energy command insider respect, which trickles down to consumer curiosity and ultimately, consumption. This is the process that renders a price tag irrelevant, which is what makes a

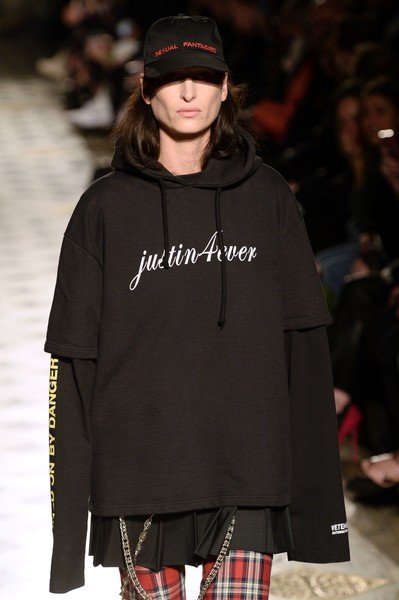

$750 Vetements sweatshirt, or $330 t-shirt “worth” the splurge. Those things aren’t just expensive activewear — they’re an excuse. A found form of validation. You want to wear a sweatshirt to fashion week because it’s cold? By all means! Now you can!

Only you never actually

couldn’t.

This lack of

confidence in our ability to think for ourselves seems like the larger problem, a sort of precursor to validation. What does it say if we need a hefty price tag to justify the acquisition of a garment? Does it mean that we still need someone to tell us what we should look like? Or simply speaking, are we back at the top where I just don’t get it? No one said you have to understand fashion to like it. I suppose that’s true of the reverse, too.

, but I wanted to post a couple remarks at least:

, but I wanted to post a couple remarks at least:

Are you in school for it?

Are you in school for it?